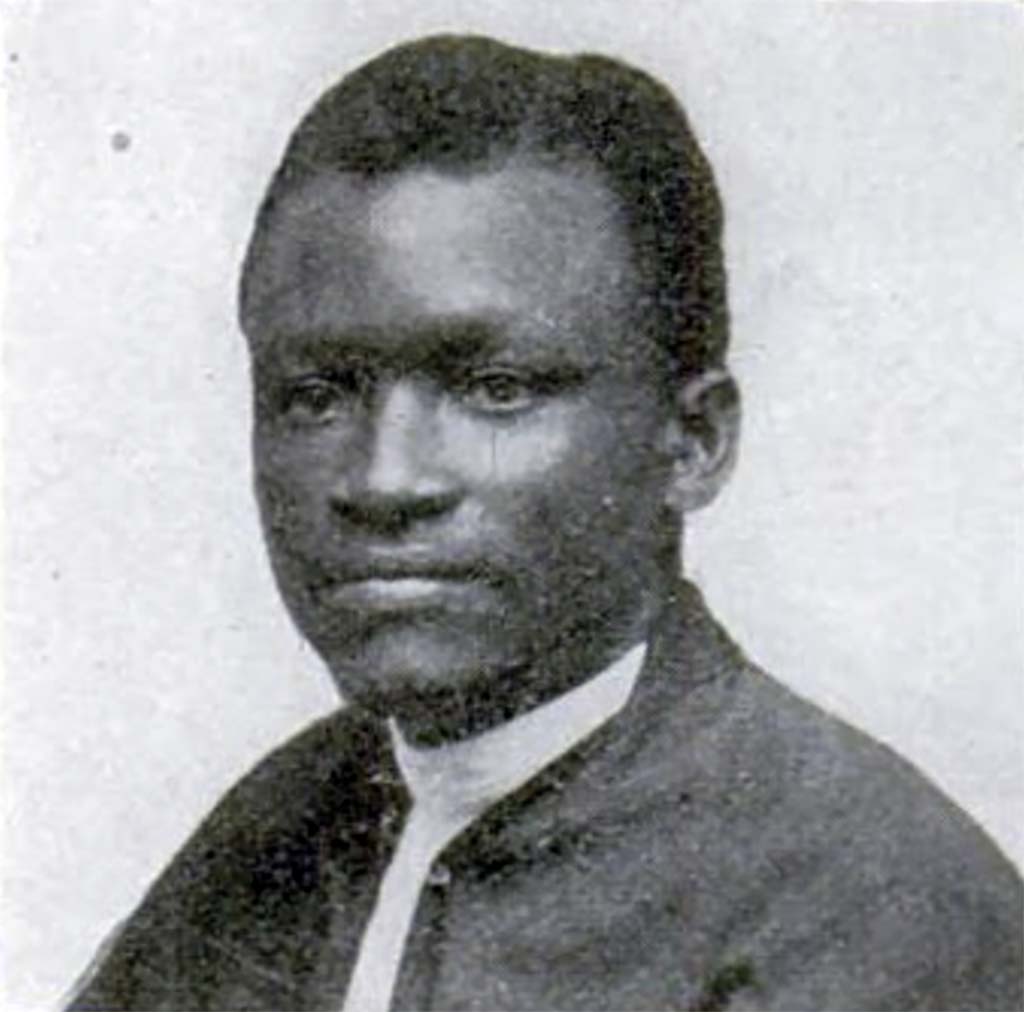

Rev. Dr. Mojola Agbebi, born April 10, 1860 as David Brown Vincent in Western Nigeria, was a leading proponent of “Ethiopianism,” which advocated an African-centered Christianity. In the 1880s, as an indication of his embrace of African culture he changed his name to Mojola Agbebi. In 1888 Agbebi was a founder of the Native Baptist Church (now the First Baptist Church), in Lagos, Nigeria. Later that year he helped establish the Ebenezer Baptist Church in that city. Agbebi was one of the first Africans to hold a degree in civil engineering from a British university but he was primarily known for his missionary work in southern Nigeria and the Cameroons between 1890 and 1910. His belief in Ethiopianism is outlined in the 1902 “Inaugural Sermon” which he gave in Lagos. That sermon appears below.

According to the Apostle’s estimate, the preaching of Christ, the triumph of the Gospel, the success of practical righteousness is the essential thing, all others are non-essentials. Let us consider one or two of the non-essentials. Formularies are non-essentials. The prayers or prayer-books of certain Christians may not necessarily be the prayers or prayer-books of other Christians. With one people it might be considered suitable to use the sign of the cross, with others it may not. The prayer-book of one nation may not be the prayer-book of another nation. The Church of Scotland antedated the Church of England by several years, yet the Anglicans never took to the formularies of the Church of Scotland. They invented their own. Nay, at some time in England there were almost as many prayer-books as there were dioceses, and there were as many and various ceremonies as the number of weeks in the year. There were once the Salisbury Prayer-book, the Bangor Prayer-book, the York Prayer-book, and the Lincoln Prayer-book. Above and beyond all this,

‘Prayer is the soul’s sincere desire, Uttered or unexpressed; Prayer is the burden of a sigh, The falling of a tear.’

And with regard to ceremonies, it is stated that

‘The great excess and multitude of them has so increased that the burden of them was intolerable… This excessive multitude of ceremonies was so great and many of them so dark, that they did more confound and darken than declare and set forth Christ’s benefits.’

In instituting such ceremonies and usages as are to be found to-day in the Anglican Prayer-book, the compilers therefore said:—

‘They condemn no other Nations, nor prescribe anything but to their own people only. For (said they), we think it convenient that every country should use such ceremonies as they shall think best to the setting forth of God’s honour and glory, and to the reducing of the people to a most perfect and godly living without error or superstition; and that they should put away other things which from time to time they perceive to be most abused as in men’s ordinances it often chanceth diversely in diverse countries.’

My friends, it is great cause for thankfulness that while a great number of people who own the Anglican Prayer-book are to-day indulging in Ritualistic practices and trudging backward to Rome, the secessions that are taking place among us are mainly towards Biblical simplicity and responsible Christianity. The ritualistic distemper is spreading in England, and one of the sincere friends of the Church Missionary Society recently wrote that

‘Many of the oldest and best friends of the Church Missionary Society have the gravest fears that it is gradually yielding to the seductions of the Ritualistic party. Many facts and circumstances point to this conclusion. One of the most striking is the disposition to work with the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, especially in meetings at home, and Ritualism simply governs and permeates every branch of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.’

Hymn-books are non-essentials to the preaching of Jesus Christ. The hymns of one nation may not necessarily be those of another nation, and they may not be put in a book. The Christians of England may sing hymns different from the Christians of Armenia, of France, or of Africa, and one tribe may sing differently from another tribe. The grave Old Hundred, which may induce solemnity in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, and the grand ‘Hallelujah Chorus,’ which has just been triumphantly rendered by your estimable choir, may both excite ridicule or disgust in a church among the Kroo. Tastes differ. English tunes and metres, English songs and hymns, some of them most unsuited to African aspiration and intelligence, have proved effective in weakening the talent for hymnology among African Christians. In one of the churches planted up-country, I have found it necessary to advise that for seven years, at least, no hymn-books but original hymns should be used at worship. African Christians dance to foreign music in their social festivities, they sing to foreign music in their churches, they march to foreign music in their funerals, and use foreign instruments to cultivate their musical aspirations. Throughout the entire scriptures there was not a case in which Christians sing foreign hymns, or an instance where prayers were unanswered or worship unaccepted because hymns were not sung. We are come to the times when religious developments demand original songs and original tunes from the African Christian. There are almost as many hymn-books as there are churches in the world, and the collections in the various hymn-books, whether of Kirk, Church, Chapel, Tabernacle or Temple are made up not only of hymns written by orthodox or Episcopalians, but by men of various denominations and sects, by Unitarians, Roman Catholics, etc. There is most presumably no book in the Christian propaganda more unsectarian or pan-denominational than the hymn-books of the churches. ‘Nearer my God to Thee,’ which has inspired and breathed consolation to saints of diverse climes and races, was written by a Unitarian believer, one who scorns the Divinity and discredits the sonship of the Lord Jesus; and ‘Lead, Kindly Light’ was written by a convert to the Roman Catholic Faith. These two would suffice for the present, out of several that could be cited. But, besides the authorship of songs and hymns, we have to deal with the character of tunes. This also is a large field for thought. No one race or nation can fix the particular kind of tunes which will be universally conducive to worship. Tunes and songs depend on the frame of mind, the breadth of soul, the experience of life, the altitude of faith, and the latitude of love of the individual. Some of the famous collections made by Mr. Ira D. Sankey, and styled ‘sacred,’ have their origin in dancing rooms and their birthplace in music halls. While we can in the language of Scripture ‘sing unto the Lord with the harp and the voice of a psalm, with trumpet and sound of cornet,’ and speak to ourselves ‘in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in our hearts to the Lord,’ we can also ‘make a joyful NOISE unto the Lord,’ and can furthermore, as the poet Thompson says, with ‘expressive silence muse his praise.’ The prophet Habakkuk says, ‘The Lord is in his holy temple, let all the Earth keep silence before him,’ and Zachariah says, ‘Be silent, 0 all flesh, before the Lord, for he is waked out of his holy habitation.’ It is, however easier and common to ‘break forth into joy’ and ‘to sing together’ than to muse the praise of God in silence. It was recorded to the early disciples that after the celebration of the Last Supper ‘they sang an hymn,’ yet it should be remembered that neither the harmonium, nor the organ, nor the piano was known to them. Our dundun and Batakoto, our Gese and Kerken, our Fajakis and Sambas, would serve admirable purposes of joy and praise if properly directed and wisely brought into play. When I visited the King of Oyo, there was a native band in one of the celebrated Kobis of the Palace. This band played at stated hours, and by special manipulation, the age, position, pedigree and circumstances of visitors are announced to the King by the drummers long before you are ushered into the presence of the King. So, also, in Central Nigeria, the King of Owo’s presence or absence, his comings in or goings out, are indicated by sounds produced on the palace drum, sounds which to the uninitiated would seem to be mere noise, but which are perfectly understood by his people. In the carrying out of the function of singing, therefore, let us always remember that we are Africans, and that we ought to sing African songs, and that in African style and fashion. The innumerable multitude in Heaven, which the Seer of Patmos saw, were of ‘all nations and kindreds and peoples and tongues,’ African, Briton, French, Icelander, and consequently were making their ascriptions each in his own tongue, only the theme of their ascriptions was one, and this idea found expression in the effusion of Dr. Watts:—

‘Come let us sing our cheerful songs, With angels round the throne, Ten thousand thousand are their tongues, But all their joys are one.’

The joys are one, Redemption is one, Christ is one, God is one, but our tongues are various and our styles innumerable. Hymn-books, therefore, are one of the non-essentials of worship. Prayer-books and hymn-books, harmonium-dedications, pew constructions, surpliced choir, the white man’s style, the white man’s name, the white man’s dress, are so many non-essentials, so many props and crutches affecting the religious manhood of the Christian African. Among the great essentials of religion are that the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, and the poor have the Gospel preached unto them. The Apostle James said: ‘Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is: “To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction and to keep one’s self unspotted from the world.”’ I would add, however, that at present the cultivation of cotton, the raising of rubber trees, of coffee, kola nuts, etc., the calling forth the riches of the soil, sanitation, and the promotion of handicrafts form part of the pressing essentials of religion.

The African Moslem, our co-religionist, though he reads the Koran in Arabic and counts his beads as our Christian brother the Roman Catholic does, and though he repeats the same formula of prayer in an unknown tongue from mosques and minarets five times a day throughout Africa, yet he spreads no common prayer before him in his devotions and carries no hymn-book in his worship of the Almighty. His dress is after the manner of the Apostles and Prophets, and his name, though indicating his faith, was never put on in a way to denationalize or degrade him. Islam is the religion of Africa. Christianity lives here by sufferance. While Islam is a bloodless faith and an iconoclastic creed, Christianity has been derided by some of its European friends as a bloody faith, the doctrine of shambles and the executioner’s creed. European Christianity is a dangerous thing. What do you think of a religion which holds a bottle of gin in one hand and a Common Prayer in another? Which carries a glass of rum as a vade-mecum to a ‘Holy’ book? A religion which points with one hand to the skies, bidding you ‘lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven,’ and while you are looking up grasps all your worldly goods with the other hand, seizes your ancestral lands, labels your forests, and places your patrimony under inexplicable legislations? A religion which indulges in swine’s flesh and yet cry Be ye holy, for I am holy.’ A religion which prays against ‘those evils which the craft and subtlety of the devil or man worketh against us,’ and yet effects to deny incantation, charms or spells and satanism—a religion which arrogates to itself censorial functions on sexual morality, and yet promotes a dance, in which one man’s wife dances in close contact, questionable proximity and improper attitude with another women’s husband. 0! Christianity, what enormities are committed in thy name.