Abner Hunt Francis was an abolitionist and activist whose life and work spanned both U.S. coasts and Canada. He was born on a farm near Flemington, New Jersey. His father, Jacob, was a Revolutionary War veteran. His mother, Mary, was enslaved when she married Jacob, who was able to purchase his wife’s freedom. While still in New Jersey, Abner opposed the American Colonization Society and attended national black conventions in 1833 and 1834. He was also a subscription agent for the Liberator.

In the 1830s, Francis moved to Buffalo, New York, where he became one of the leading members of the local abolitionist movement and an avid supporter of initiatives that aimed to secure civil rights for African Americans. He continued to support national black conventions that he now attended and co-organized as an official representative of Western New York organizations. In 1840 he was actively involved in proposing a petition to secure unrestricted voting rights for all male citizens of twenty-one years of age in New York, “irrespective of color or conditions.” Abner’s speech at a meeting in support of the petition reportedly “created deep feelings throughout the house.” He was also one of the co-organizers of the 1843 National Convention hosted in Buffalo. The convention was a site of the dramatic vote that rejected Henry Highland Garnet’s resolution calling for the enslaved to revolt and decided by a narrow margin to advocate the position of nonviolence. As a prominent member of the Buffalo City Anti-Slavery Society, Abner was also one of the leaders of the local movement opposing segregation in schools. Public meetings that called for integrated schools were common in Buffalo, and Abner used his position to fuel the ongoing battle. He collaborated with Frederick Douglass and remained a critic of the emigrationist movement.

When in Western New York, Abner married Sydna Edmonia Robella Dandridge who was also engaged in a number of social and political initiatives. In Buffalo, she served as secretary of the Female Dorcas Society and president of the Ladies’ Literary and Progressive Improvement Society of Buffalo. The Francis couple had one daughter, Theodosia.

Apart from his political activism, Francis was also an entrepreneur. In Buffalo, he was an agent for two black newspapers, the Colored American and the North Star. In 1836 when he most likely moved to Buffalo, he is listed in the city directory as a barber. In 1839 after two years spent in R Banks & Co., he and his partner James Garrett started Francis, Garrett & Co. (later Francis and Garrett), a successful clothing store in Buffalo downtown. Although evidence exists that Abner relocated to Portland, Oregon, in 1851, Buffalo’s city directories continue to list Abner H. Francis (also as A.H. Francis) until 1853. While Martin Delany notes that Francis and Garrett lost their business in 1849, Buffalo’s city records suggest that it may have taken place in 1847 or 1848. That year, Abner is already listed as a foreman under a new address of residence.

Shortly after the census of 1850, Abner Hunt Francis and his wife arrived in Portland, Oregon. Soon after their arrival, the family was targeted for judicial expulsion based on a territorial black exclusion law adopted in 1849. In September 1851, Judge O.C. Pratt ordered their departure within four months. A petition drive was mounted by Portland residents to convince the legislature to allow an exemption for the family; 211 individuals signed the petition. After extensive debate, the legislature tabled the request and never revisited the issue.

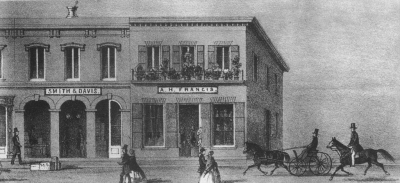

Francis may have briefly returned to Buffalo. Evidence suggests that between 1850 and 1852, he worked as an agent at D.P. Brown’s medical depot there. He returned to Portland, however, where he owned and operated a successful mercantile business at the corner of Front and Stark streets in the city.

By 1860 Francis had amassed in real estate and personal property a fortune estimated at $36,000. In 1860 Francis migrated to Victoria, British Columbia, perhaps motivated by the presence there of James Douglass, of mixed racial ancestry himself, who was governor. Francis fared less well economically in Victoria, having to declare bankruptcy in 1862, but from his arrival until his death there in 1872, he was a recognized leader in the black immigrant community in political and social activities.