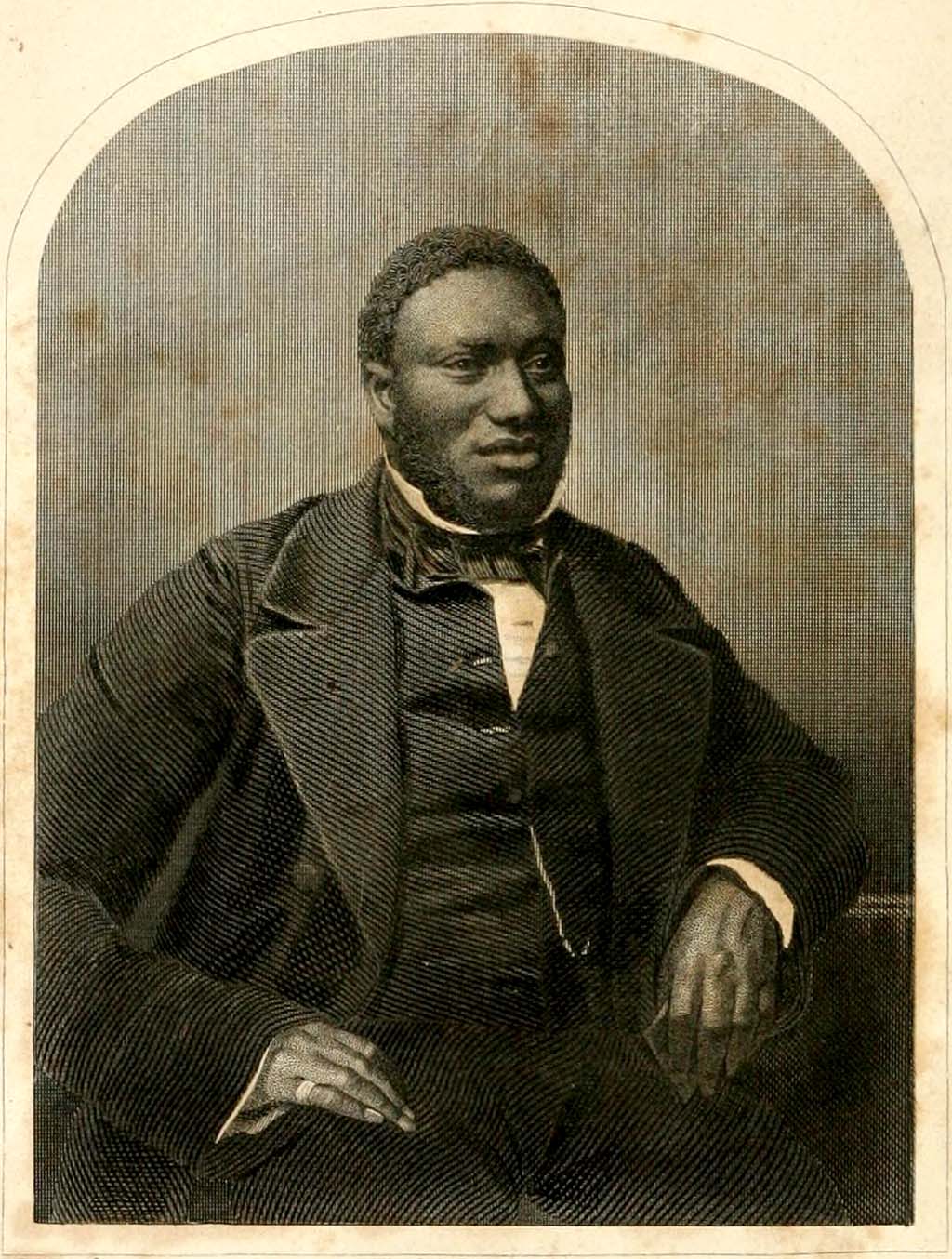

Holata Micco is widely considered a descendant of the “Seminole” founding Hitchiti-speaking Oconee family of “Cowkeeper” of Cuscowilla Town on the Alachua Pains of Spanish Florida. The name that Holata was best known by, “Billy Bowlegs,” uniquely united the whole experience of the three “Seminole wars” and also uniquely connected the epic stories of “The Trails of Tears” and “The Trail of Blood on Ice.” Holata himself likely died in 1859, before the last of these episodes. However, a successor chief, Sonaki Micco, adopted the Billy Bowlegs name, and carried it forward to a warrior’s glory during the 1861/62 “Great Escape” on the “Trail of Blood on Ice” to Kansas, and through the subsequent heroic contributions of the Union‘s Indian Home Guards Regiments during the Civil War.

In his childhood Holata experienced years of bloodshed and displacements in the “First Seminole War” that gradually diminished after 1818 as Andrew Jackson annexed much of the Territory. Now, as a Micco, Holata took a lead in the hostilities of “The Second Seminole War” from 1835-1842, the most costly conflict in American history prior to the Civil War and was deemed by the U.S. Commander Jessup to be “a Negro-not an Indian war.” Holata Micco was a friend of Osceola, the principal Seminole commander during most of the war, and of Osceola’s closest comrades, Wildcat and Alligator, and the Black Seminole leaders Abraham and John Caballo Horse. Holata was among them when the Seminole leadership was twice taken prisoners during “peace negotiations” but twice escaped. In December of 1837, as part of that war, John Horse led the largest and most successful slave rebellion in American history. At least 385 escaped black slaves joined over 500 black Seminole warriors in completely destroying five of the largest plantations in Florida and seriously damaging ten more.

Following the Second War, despite later appeals by his friends, Wildcat and John Horse, Holata Micco refused to “remove” his band to Indian Territory on “the Trail of Tears.” Micco’s and Arpeika’s bands were subsequently confined to a small reservation in the Florida swamps. Holata’s renewed resistance in mid 1855 has been termed the “Third Seminole War.” After nearly three years of fighting, he accepted a financial settlement and his band would also experience the Trail of Tears. Reportedly, he died soon thereafter. Only Arpeika’s small band remained in the swamps, whose descendants are today’s Florida Seminoles. Prior to the Civil War, pro-slavery leaders came to power among the Seminoles, as with the other four nations in Indian Territory. All five nations joined the Confederacy. Sonaki Micco, under his new alias “Billy Bowlegs,” with Holata’s old friend Halleck Tusteneggee, and hundreds of Seminoles, joined with the anti-Confederacy Creek leader Opothlayahola and thousands of Indians and blacks in a “Great Escape” to Kansas. The Seminole warriors were among most fierce fighters in their three major battles against Confederate units. However, they were routed in the third battle and their followers left a “Trail of Blood on Ice” as they struggled to reach Kansas.

Once there these warriors then formed “Indian Home Guard” regiments of the Union army, and joined with two Kansas Colored Regiments to liberate Indian Territory. In 1862, they were the first Union soldiers of color to actually to engage in armed battle against Confederate troops. Billy-Bowlegs’/Sonaki Micco’s bravery and military leadership during the Civil War was officially commended. He died of illness (probably smallpox) in 1864, and was buried at Ft. Gibson in Indian Territory.