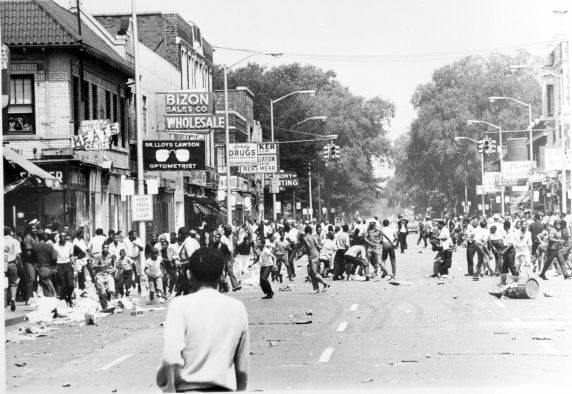

The Detroit Race Riot in Detroit, Michigan in the summer of 1967 was one of the most violent urban revolts in the 20th century. It came as an immediate response to police brutality but underlying conditions including segregated housing and schools and rising black unemployment helped drive the anger of the rioters.

On Sunday evening, July 23, the Detroit Police Vice Squad officers raided an after-hours “blind pig,” an unlicensed bar on the corner of 12th Street and Clairmount Avenue in the center of the city’s oldest and poorest black neighborhood. A party at the bar was in progress to celebrate the return of two black servicemen from Vietnam. Although officers had expected a few patrons would be inside they found and arrested all 82 people attending the party. As they were being transported from the scene by police, a crowd of about 200 people gathered outside agitated by rumors that police used excessive force during the 12th Street bar raid. Shortly after 5:00 a.m., an empty bottle was thrown into the rear window of a police car, and then a waste basket was thrown through a storefront window.

At 5:20 a.m. additional police officers were sent to 12th Street to stop the growing violence. By mid-morning looting and window-smashing spread out along 12th Street. As the violence escalated into the afternoon, Detroit Congressman John Conyers climbed atop a car in the middle of 12th Street to address the crowd. As he was speaking, the police informed him that they could not guarantee his safety as he was pelted with bricks and bottles.

Around 1:00 p.m. police officers began to report injuries from stones, bottles, and other objects that were thrown at them. When firemen responded to fire alarms, they too were struck with thrown objects. Mayor Jerome Cavanaugh met with city and state leaders at police headquarters and agreed that additional force was needed in order to stop the violence. By 3:00 p.m. 360 police officers began to assemble at the Detroit Armory as the rioting spread from 12th Street to other areas of the city. The fires started during the riot spread rapidly in the afternoon heat and as 25 mile per hour winds began to blow. Even as businesses and homes went up in flames, firemen were increasingly subject to attack by the rioters.

At 5:30 p.m., twelve hours into the riot, Mayor Cavanaugh requested that the National Guard be brought into Detroit to stop the violence. Meanwhile firefighters abandoned an area roughly 100 square blocks in size around 12th Street as the fires raged out of control. The first troops arrived in the city at 7:00 p.m. and 45 minutes later the Mayor instituted a curfew between 9:00 p.m and 5:00 a.m. Seven minutes into the curfew a 16-year-old African American boy was the first gunshot victim.

At 11:00 p.m. a 45-year-old white man was seen looting a store and was shot by the store owner. Before dawn, four other store looters were shot, one while struggling with the police. As the night wore on, there were reports of deaths by snipers and complaints of sniper fire. Many of these reports were from policemen who were unable to determine the origins of the gunfire.

At 2:00 a.m. Monday morning, 800 State Police Officers and 8,000 National Guardsmen were ordered to the city by Michigan Governor George Romney. They were later augmented by 4,700 paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division ordered in by President Lyndon Johnson. With their arrival the looting and arson began to end but there were continuous reports of sniper fire. The sniper attacks stopped only with the end of the violence on Thursday, July 27th. The Mayor lifted the curfew on Tuesday, August 1 and the National Guardsmen left the city.

In the five days and nights of violence 33 blacks and 10 whites were killed, 1,189 were injured and over 7,200 people were arrested. Approximately 2,500 stores were looted and the total property damage was estimated at about $32 million. Until the riots following the death of Dr. Martin Luther King in April 1968, the Detroit Race Riot stood as the largest urban uprising of the 1960s.