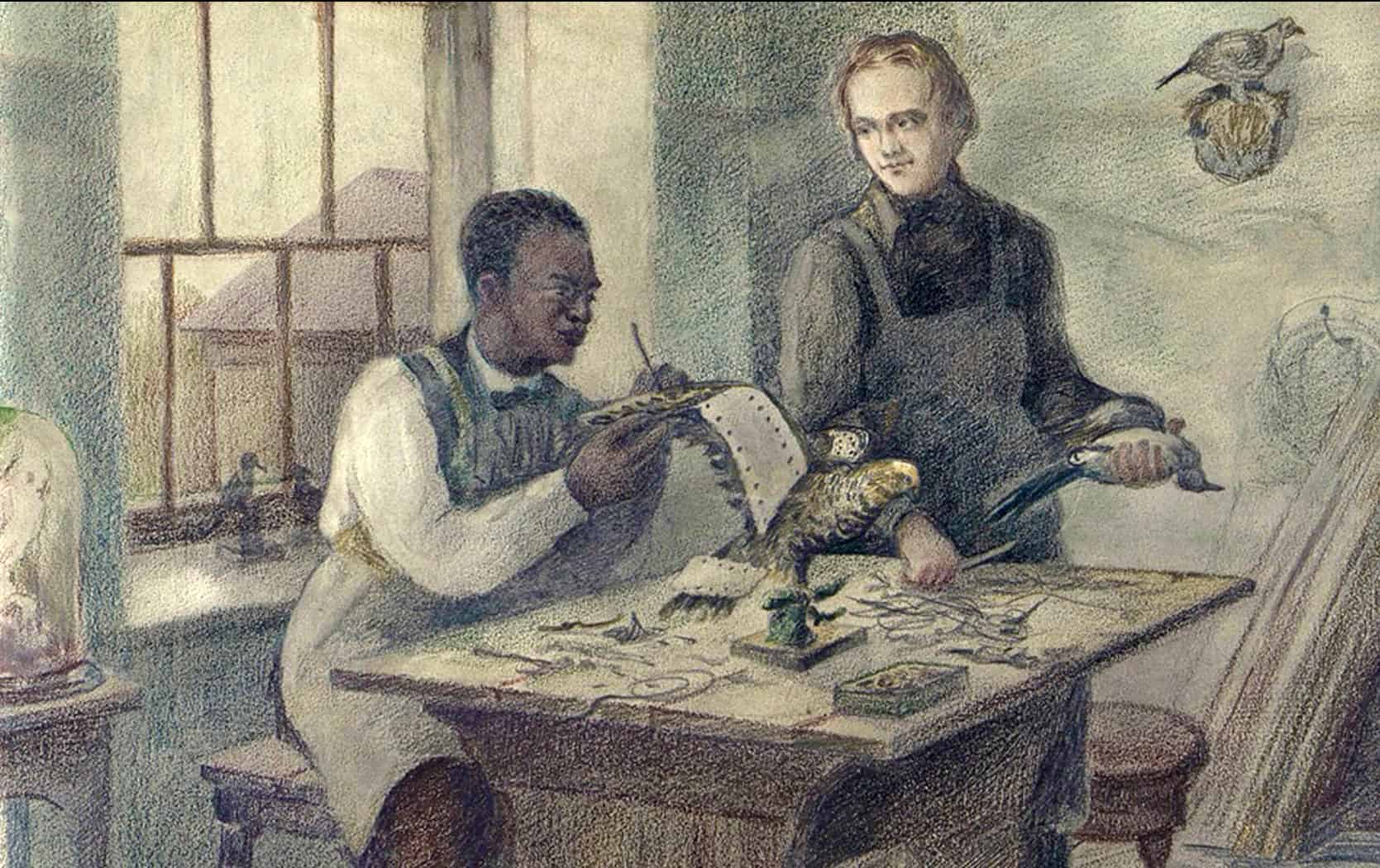

Gobo Fango was born in the Eastern Cape Colony in what is now South Africa around 1855, just before the beginning of the eighth of the nine Xhosa Wars (Cape Frontier Wars) against British and Boer settlers. Fango was a member of the Gcaleka tribe, a sub-group of the Xhosa people. These frontier wars brought poverty and privation to the Xhosa people, forcing his starving mother to abandon him at the age of three, leaving him in the crotch of a tree where he was found by the sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers on the Cape Frontier. They claimed him and raised him as an indentured servant. Two years later, in 1857, the Talbot family was baptized by Latter Day Saint (LDS) missionaries. Shortly afterward, the Talbots sold their belongings and prepared for the migration to Utah Territory. On February 20, 1861, they boarded the ship Race Horse, bound for Boston, Massachusetts, and from there took a train to Chicago, Illinois. Arriving in Chicago on the eve of the Civil War, abolitionists accused the Talbots of bringing a slave across the free states, forcing them to hide the six-year-old under a passenger’s skirt until the search ended.

The Talbot family continued west through Iowa and to Florence, Nebraska Territory, and outfitted wagons for their remaining trek to Utah. They arrived in Salt Lake City on September 13, 1861, and eventually settled in Kaysville, Utah, where Fango worked as a farm laborer for the Talbots. Because he slept in a shed, his feet were frozen, forcing him to walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

When Fango was a teenager, the Talbots sold him to the Lewis Whitesides family even though he was officially freed at the age of seven when the U.S. Congress abolished slavery and indentured servitude in all U.S. territories, including Utah. Fango was sold again (illegally) to Ruth Whitesides Hunter and brought to Grantsville, where he helped with the family’s sheep herding. By the early 1880s, he had settled in the Goose Creek Valley in Idaho Territory. By this point, Fango was free of any obligations to others and ran his own sheep-herding ranch.

The longstanding region-wide rivalry between cattlemen and sheep herders eventually involved Fango when, in 1886, cattlemen in Goose Creek issued an edict demanding the departure of all sheepmen from the valley. When cowman Frank Bedke accused Fango of trespassing on land reserved for cattle grazing, Fango asked for evidence of Bedke’s ownership of the land. Bedke, in response, shot Fango. Mortally wounded, Fango crawled to a farmhouse where he dictated his will, leaving money to several members of the Hunter family, to the Salt Lake LDS Temple fund, and to the “needy poor people.”

Bedke was brought up on charges of murder, but the jury could not reach a unanimous verdict. In a second trial, the jury found that Bedke had killed Gobo Fango in an act of self-defense, and he was acquitted.

Gobo Fango came to the western United States because of the Talbots’ Mormon conversion, and his story has been used in multiple ways (often inaccurately) to teach faith. In fact, there is no record that he was baptized. Those who believe he was lovingly “adopted” presume that he had been baptized. The fact that he apparently hadn’t been indicates that his story is actually one of slavery, re-cast as one of a white family tenderly caring for an abandoned Black boy.

Fango’s grave in the Oakley, Idaho, cemetery is marked: “Gobo Fango died February 10, 1886, 30 years old.”