In 1852, California legislators passed a harsh fugitive slave law that condemned dozens of African American migrants to deportation and lifelong slavery. Historian Stacey L. Smith examines the legal travails of three accused fugitive slaves to illuminate the social relations of slavery in gold rush California and the consequences of the fugitive slave law for the state’s African American population.

Americans have long imagined gold rush California as a landscape of liberty, a place where individuals could escape the economic and social inequality east of the Rockies and find almost unlimited opportunities for financial independence and upward mobility. Indeed, for Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins, and Sandy Jones, three former slaves from Mississippi, the gold rush seemed to present unprecedented possibilities for securing freedom and economic self-sufficiency. After arriving in the small mining town of Ophir, California, in 1851, the three men built a booming freight business hauling supplies across California’s northern gold country. Within a few months, they amassed over $3,000 in personal property, including a mule team and wagon.

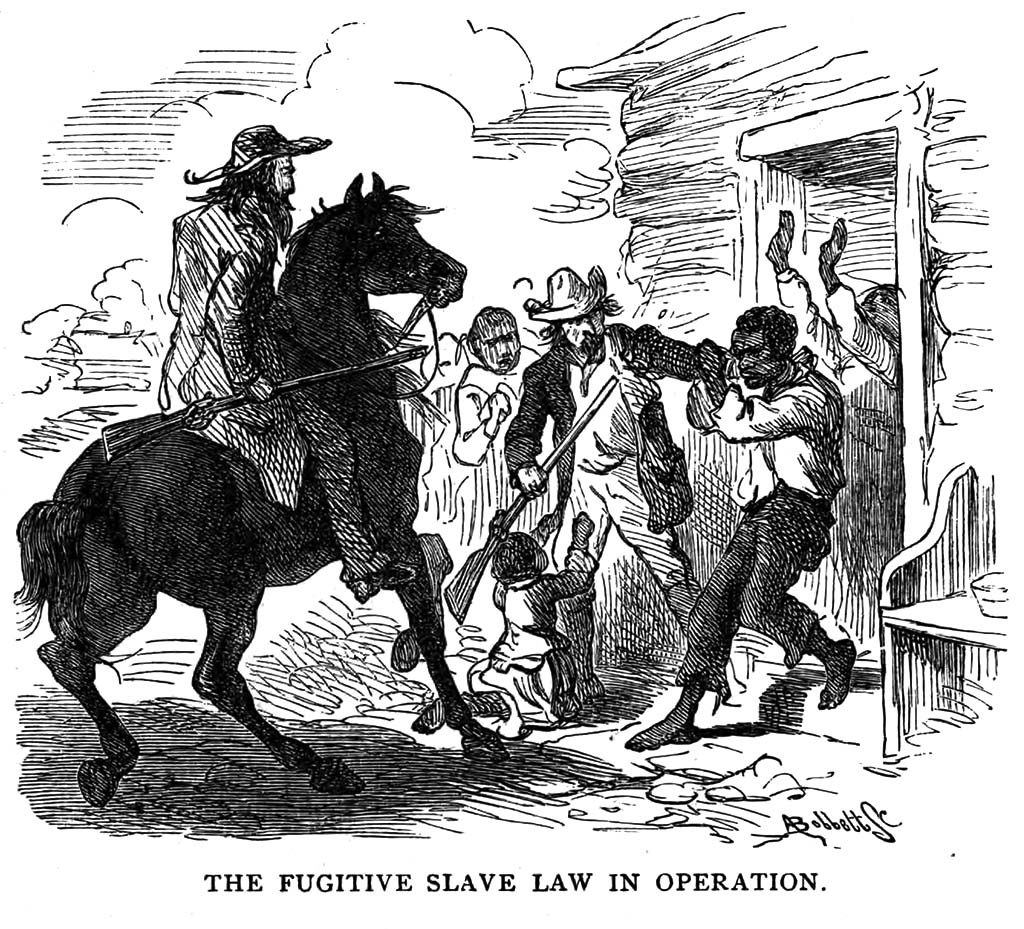

The African American men’s dreams of California freedom ended abruptly in the middle of the night on April 31, 1852. While the three men slept, a group of armed whites broke into their cabin. The invaders tied up the black men, loaded them into their own wagon, and hauled them to Sacramento using their own mule team. There, a justice of the peace pronounced the men to be fugitive slaves and ordered their deportation back to the Slave South.

The African American men likely knew at least of one of their captors. Green Perkins, the leader of the midnight raid, was the first cousin of Charles Perkins, the man who had brought the African Americans to California in the first place. Charles Perkins belonged to a Mississippi slaveholding family and he had traveled to California to dig gold in 1849. Like many young slaveholding men, Perkins depended on networks of family capital to make his California journey profitable. Charles’s father, W.P. Perkins, loaned his son the twenty-one-year-old enslaved man, Carter Perkins, to aid him in his California ventures. In a pattern common to the Slave South, Charles Perkins’s initial journey to California paved the way for a chain migration of his slaveholding kin and friends who all settled near each other in the mines. Two of these Mississippi friends brought two other enslaved men from the Perkins plantation to work in California. Aged forty-two and fifty-seven, respectively, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones left behind wives and children in the South.

The Perkins slaves worked for Charles Perkins in the gold mines, helping him to build a fortune in gold that he probably hoped would allow him to buy land and slaves of his own one day. But the young man’s California venture apparently proved unprofitable. Only able to pay for his own passage home, he left the three enslaved men behind and departed for Mississippi in the spring of 1851. Like other slaveholders who hoped to keep their bondpeople from running away in the mines, Charles Perkins struck an informal emancipation bargain with the men. If the three slaves worked faithfully for six months under the supervision of one of Perkins’s friends, they would earn their freedom. Accordingly, Perkins’s friend released the men in November of 1851.

Like other enslaved people who struck similar bargains with their masters, the three black men probably assumed that their freedom was secure. After all, California entered the Union in 1850 with a state constitution that banned slavery. Within less than a year of statehood, however, white southern-born politicians began to agitate for legal protections for masters who had taken their bondpeople into California when it was still a federal territory. Led by assemblyman Henry Crabb, a proslavery Whig from Tennessee, these southerners asserted that the federal territories were the common property of all American citizens. Echoing the arguments of the Slave South’s most vocal spokesman, John C. Calhoun, they insisted that the U.S. Constitution guaranteed slaveholders the right to travel with their slave property into any federal territory. Neither Congress nor territorial governments could close slavery out of the territories. They therefore argued that California’s new antislavery constitution could not deprive masters of slaves who they brought before official statehood in September of 1850.

Crabb and his southern-born allies in the proslavery branch of California’s Democratic Party pushed for a state fugitive slave law that would allow masters to hold the slaves who they had brought to California before statehood and take them back to the South. Any enslaved person who resisted this process would be criminalized as a fugitive slave.

Crabb’s bill passed the assembly in 1852, but it hit a roadblock in the senate. There, David C. Broderick and his faction of the California Democratic Party united to kill the legislation. Overwhelmingly northern-born and eager to preserve California as a haven for free white laborers, the Broderick faction supported free soil policies that would keep slavery out of the West. Broderick used his mastery of parliamentary procedure to obstruct the bill. Southern-born Democrats managed to outmaneuver Broderick and won moderates to their side by appending a “sunset clause” to the bill. This clause stipulated that masters would have only one year to claim their slaves and remove them from the state. They could not hold slave property in California indefinitely. Optimistic that the new law struck a careful balance between protecting slaveholder rights and preserving California’s antislavery constitution, moderates joined proslavery men in passing the law. It went into effect on April 15, 1852.

It is unclear whether Charles Perkins’s former slaves were aware of the new law that threw their status as free men in jeopardy. We do know that Charles Perkins—now back in Mississippi—learned about the passage of the law from slaveholding relatives who remained behind in California. Perkins sent a letter to his cousin, Green Perkins, giving him power of attorney to seize the men on his behalf and send them back to Mississippi. Green Perkins enlisted the aid of the Placer County sheriff to carry out the midnight raid on the African American men’s cabin and found a sympathetic justice of the peace to authorize their deportation as fugitive slaves.

Before Green Perkins could make good on his promise to send the men back to Mississippi, members of Sacramento’s small African American community caught wind of the men’s plight. They enlisted the help of a white antislavery attorney named Cornelius Cole. Cole and his partners launched a suit in the Sacramento District Court aimed at testing the validity of the fugitive slave law under California’s antislavery constitution. Once the men got their day in court, a proslavery mob intimidated the presiding judge and he found in favor of the slaveholder. With financial backing from free African Americans, Cole and his colleagues appealed to the California Supreme Court.

Justice proved illusory in the state’s highest court as well. Hugh C. Murray of Missouri and Alexander Anderson of Tennessee, the two justices who presided over the case of In re Perkins were southern-born Democrats. They ruled that the fugitive slave law was, in fact, constitutional. In granting slaveholders a reasonable amount of time to reclaim slaves brought in before statehood, the law was wholly consonant with the U.S. Constitution. Moreover, they found that the antislavery clause of California’s constitution was a mere “declaration of a principle.” It contained no enforcement clause that explicitly freed slaves who came to the state and so was “inert and inoperative.” The court found in favor of the slaveholder. Perkins’s agents took custody of the men and departed for Mississippi.

Robert Perkins, Carter Perkins, and Sandy Jones may have eventually succeeded in seizing their freedom. One newspaper correspondent reported that the men ran away when their ship stopped in Panama. Regardless of the men’s ultimate fate, the legal case testing the constitutionality of the state fugitive slave law had far-reaching legal consequences for California’s 2,000 black residents. Nearly all African Americans who came to California as slaves arrived during the pre-statehood torrent of goldseekers in 1849-50 and were susceptible to deportation. Even free African Americans could easily fall victim to kidnapping and fraud because California’s black codes prohibited them from testifying against whites in state courts. Most importantly, the law’s sunset clause proved malleable in the hands of proslavery politicians. In 1853, and again in 1854, the state legislature voted to extend the fugitive slave law another year. Slaveholders had until the spring of 1855 to claim and remove their slaves, making enslaved people vulnerable to deportation five or six years after most had arrived on California soil. Newspapers reported stories of nearly two dozen slaves arrested and sent back to the South between 1852 and 1855. Even after the lapse of the fugitive slave law in 1855, masters informally held slaves in California until 1864.

California’s fugitive slave law undermines the persistent myths of westering freedom that continue to shape American memory of both regional and national history. Most renderings of the sectional crisis and the Civil War treat California, and the Far West more generally, as isolated outposts of frontier freedom that were distant from and irrelevant to the national cataclysm over slavery. The travails of the Perkins slaves reveal, however, that the struggle over slavery was a truly national phenomenon that shaped the political, legal, and economic destinies of black and white Americans across the North, South, and West.